![]()

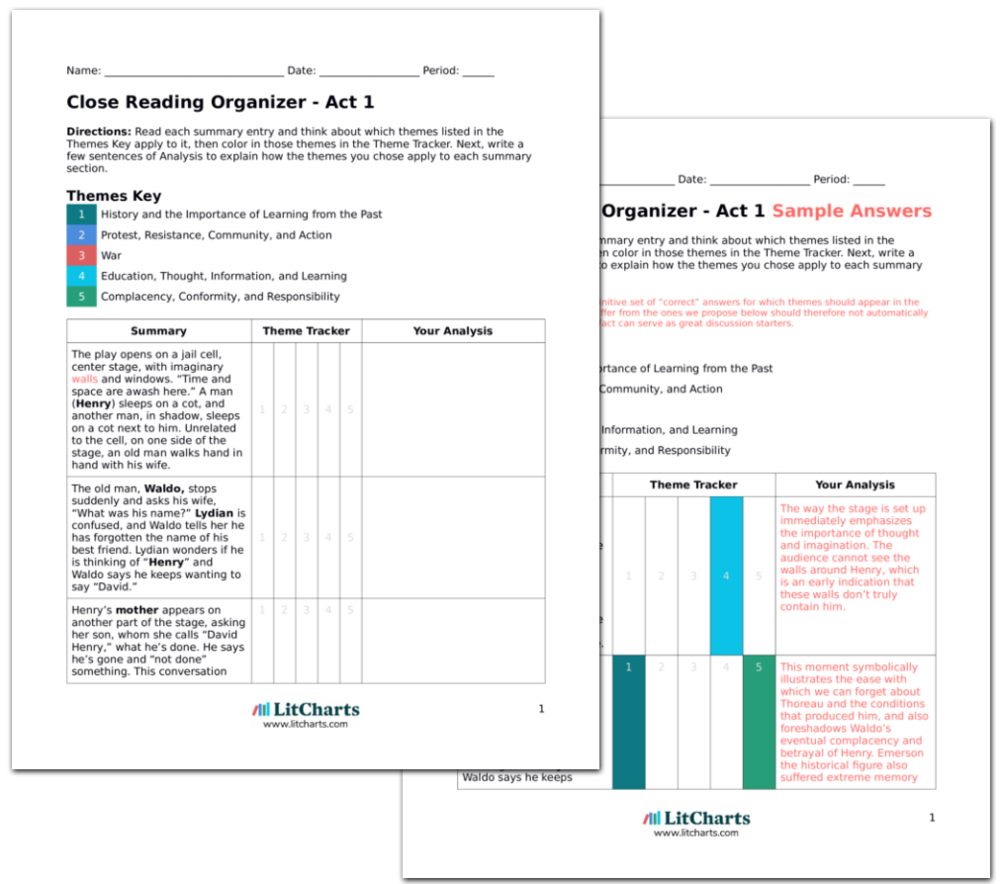

LitCharts assigns a color and icon to each theme in The Night Thoreau Spent in Jail, which you can use to track the themes throughout the work.

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

Lights rise on Henry in the jail cell . Bailey is asleep. Henry is pacing and thinking aloud. He laughs at the notion that the government has taken his freedom. He is free, he says. He can touch his nose if he likes. He can stand up or sit down. And his thoughts cannot be contained by walls—he can think whatever he wants.

The jail cell is perhaps the reconciliation of Henry’s desire to live outside society and also effect change within it. The jail is both within and without—it separates Henry without containing him, and gives him clarity without totally removing him.

Active Themes![]()

![]()

![]()

Lydian enters, and tells Henry he should “go along.” Henry erupts angrily, shouting “GO ALONG” at her. Then Lydian asks him to take Edward with him. Henry saunters out of the cell into the imaginary meadow, which he now shares with young Edward. Henry teaches Edward how to find the best huckleberries (by “knowing where to stand”) and Edward runs around picking them up excitedly. He quickly fills his whole basket, but in his excitement he trips and spills them. When he starts to cry, Henry comforts him by saying that he has planted a whole new field of huckleberries.

Henry, though he is no longer a teacher, is responsible for the education of Waldo’s son. Henry proves to be a good mentor to Edward, and there is the suggestion that Henry is less of an isolationist than he seems. His affection for Edward and his investment in Edward’s education is clear to see.

Active Themes![]()

![]()

Edward is comforted, and tells Henry he wishes he were his father. The light fades on them and rises on Lydian , writing a letter at her desk. Henry and Edward arrive home, and Edward tells Lydian that he’s asked Henry to be his father. Lydian lightly asks Edward, what about his real father? Edward complains that Waldo is never around because he is always traveling and making speeches. He also asks his mother if she wouldn’t be happier if Henry was her husband.

The irony is that Waldo, who is so concerned about the impressions he makes on strangers in his audience, has not even made a good impression on his own son. The implication is that there are personal (in addition to political) consequences of desiring only to be liked.

Active Themes![]()

![]()

Things become awkward between Lydian and Henry . She says perhaps he should not work around the house while Waldo is away. Henry tells her not to be afraid of him, then remarks that he has too much respect for her. Love is everywhere and has no schedule, he notes, somewhat enigmatically. Lydian asks him why, if love is everywhere, does he choose to be alone?

Lydian is the first character in the play to directly question Henry’s choice to seclude himself entirely from community, family, and love. Henry will eventually reject his secluded life at the end of the play, making this conversation especially significant.

Active Themes![]()

"My students can't get enough of your charts and their results have gone through the roof." -Graham S.

Suddenly Edward , who has wandered outside, runs back in holding a chicken, saying the chicken is wearing gloves. Lydian says this can’t be possible, but upon inspection realizes the chicken is in fact wearing gloves . Henry explains that he’d heard her complaining about the chickens scratching at her rose plants, and so had fitted their feet with homemade gloves.

Henry’s solution to the problem of the chickens is strange to Lydian, but also notably effective. The message is that we should not reject ideas simply because they seem strange, for if we remain open to strange solutions, we can benefit from them.

Active Themes![]()

![]()

![]()

Lydian , pleading now, tells Henry to get married—to find someone to love. She doesn’t want him to be lonely. Henry says he cannot be lonely any more than the north wind can be lonely. He then asks her if she is not lonely, going to bed every night without her absent husband. He touches her sleeve and asks her if it is not a pity that she is so “safe” around him.

This is another moment where we can see Henry not only criticizing but almost betraying his mentor. His independence is beginning to become more definite.

Active Themes![]()

![]()

![]()

Lights fade and come back up on the cell , where Henry and Bailey once again sit. Bailey asks Henry to be his lawyer, but Henry says he cannot be a lawyer. Bailey begs Henry to tell him what to do, and Henry suggests being born in a more just time. He then suggests prayer, and Bailey agrees. Henry delivers a wry, almost sarcastic prayer, telling God that Bailey deserves better than what God has given him.

The suggestion that there is a “more just time” into which Bailey can be born directs the audience’s attention to the similarities between Thoreau’s time and their own. The implied suggestion is that even now we have not yet seen the “more just time” Henry is hoping for.

Active Themes![]()

As Bailey sinks back onto his cot, the lights come up on Henry and he moves out of the cell into the sunny meadow once again. A man, Williams , comes out of the woods. He is an escaped slave. He tells Henry he needs food so he has enough strength to get to “Cañada,” where he can be free. Henry tells him to help himself to bread inside the cabin. Williams is startled at Henry’s trust, but goes inside and takes the bread anyway. He comes out chewing ravenously.

The added Spanish “tilde” to Canada suggests an affinity between the mistreatment of African-Americans and the misconduct on the part of the U.S. government in the Mexican-American War. The suggestion is that American injustices are all part of the same historical lineage, and a result of not learning from past mistakes.

Active Themes![]()

![]()

Henry tells Williams that he is glad he has escaped. Williams asks Henry why he lives in a “slave shack.” Henry, amused, says that he is rich, but not with money. Henry then says that Williams needs a first name, now that he is free. Williams suggests “Mr. Henry’s Williams” to which Henry angrily says “No!” He tells Williams that he doesn’t belong to anyone anymore. But Williams likes the sound of “Henry Williams,” and shouts the name to the sky.

Henry will not allow Williams to become like him. In other words, he will not allow the dynamic that existed between him and Waldo to be reproduced. Henry does not want students who try to follow or imitate him—he wants freedom for everyone.

Active Themes![]()

Williams says he wants to stay here with Henry , where he feels free. But Henry says that in Massachusetts, his blackness is a red flag, and he must find a Walden somewhere where “sickening laws” against blacks don’t exist. He tells Williams to “go to Can-ya-da!” The lights fade on them.

Because Williams cannot go to another time, he must go to another place. But again the pronunciation of Canada—as though there were a Mexican tilde over the “n”—suggests a morbid end for Williams, as history continues to repeat itself.

Active Themes![]()

The lights come up on Henry and Waldo in the midst of an argument. Waldo is insisting that he’s “cast his vote” and there is nothing more he can do. Henry tells him to vote with his voice, and use his influence to speak out against segregation. It becomes clear through their argument that Williams has been killed jumping from a moving train in his attempt to get to Canada. Henry argues that for Waldo, Williams is merely an abstraction—fodder for a lecture, but not a human, not a real tragedy.

The differences between Henry’s philosophy and activism and Waldo’s is made very clear in this argument. Waldo will not create trouble the way Henry has, and soothes himself by thinking of tragedies only in the abstract. The suggestion to the audience is that it is all too easy to think of war as abstract, and so avoid contending with the reality of it.

Active Themes![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

Henry pleads with Waldo —he is an Emerson, and he can make a difference if he would only use his voice. Waldo contemplatively notes that Henry lives the way Waldo talks. Henry becomes even angrier at Waldo, and Waldo retorts that Henry is not exactly inciting rebellion by retiring to the woods. Henry has no reply to this criticism. Waldo gently tells him that they must work within the existing framework in order to effect change. This disgusts Henry. He tells Waldo he was wrong about him, and starts to leave. Waldo, in pain, asks Henry what he should do. Henry tells him he must go to Concord Square and declare himself against the war and against segregation.

Waldo, in his turn, has a valid criticism for Henry as well. He notes that Henry is not effecting change very well by disappearing. The difference, however, is that Henry appears to take this criticism to heart at the end of the play, whereas Waldo never reforms his worldview—he remains too concerned with public opinion to speak out in meaningful ways against the American government and the War. To Henry’s mind, this makes him just as guilty as the U.S. government itself.

Active Themes![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

Lights come up in the center of the stage, where Henry is rallying a crowd of people, telling them that Waldo will be making an important announcement. The crowd grows restless as time passes and there is no sign of Waldo. Lydian enters, and tells a crestfallen Henry that Waldo needs more time to “meditate” on these matters. Henry tells Lydian that Waldo is “drowning in his own success.”

This disappointment cements the rift between Henry and the teacher he was once prepared to follow. Waldo cannot give up his success and his good name, even in the name of human life and America’s integrity. This is why Henry says Waldo is “drowning in success.”

Active Themes![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

Henry shouts to the citizens of Concord, trying to get their attention, but there is no one there. He grips the rope of a bell to ring it, but it makes no sound. A drummer boy enters, and a chant becomes audible: “hate-two-three-four!” A sergeant is handing Bailey a gun, insisting that he must learn to kill. Bailey resists, but a crowd of people turn on him, calling him a coward and a traitor. The sergeant is Sam and the General is Ball .

The action becomes dream-like and highly symbolic here. In the dream, the citizens of Concord are no longer just indirectly responsible for the violence in Mexico, but now directly perpetrating it. Their complacency is, in the dream, literal, direct guilt.

Active Themes![]()

![]()

The sergeant forces a musket into Henr y’s hands. Henry resists, but his mother appears and tells him to “always do the right thing, even if it’s wrong.” Then the President appears: it’s Waldo . Everyone begins to chant “go along” with “demonic glee.” They begin to attack a Mexican soldier ( Williams ) but he escapes. Henry pleads with the president—Williams only wanted to gather huckleberries, Henry says. The president promises to write a lengthy essay on the subject.

The play, via this hellish dreamscape, takes every character to task for their hypocrisy. Mrs. Thoreau is exposed to care about “rightness” only in the sense of propriety, and not in a moral sense. Waldo, meanwhile, is made president—the man chiefly responsible for the violence—because he has refused to use his immense influence to protest the war.

Active Themes![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

Henry notices his brother John in the ranks, but just as he does, a volley of shots are heard. John is shot and Henry pleads with God not to let John die—“not again.” The whole stage fades into darkness.

John dies again, and the suggestion here is that a soldier’s death is as meaningless and accidental as death from a shaving cut.

Active Themes![]()

![]()

Sam is waking Henry up from a bad dream. He tells Henry his taxes have been paid by his Aunt Louisa. Henry doesn’t want to go, but agrees to leave on the condition that Bailey is granted a speedy trial. Sam agrees. Henry and Bailey say their goodbyes. Bailey asks Henry if he will go back to the pond, but Henry says no. He feels he has “several more lives to live” and is worried that if he becomes too comfortable at Walden, he will spend all of them there. “Escape is like sleep,” says Henry, “and when sleep is permanent, it’s death.”

Henry decides to leave Walden, taking Waldo’s criticism to heart and deciding to not run away anymore. The suggestion that Thoreau has “several more lives to live” is once again a call to the audience to revive Henry Thoreau in their contemporary moment, and to apply his philosophy (as it is outlined in this play) to their own activism.

Active Themes![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

“Would not have made it through AP Literature without the printable PDFs. They're like having in-class notes for every discussion!”

Get the Teacher Edition

“This is absolutely THE best teacher resource I have ever purchased. My students love how organized the handouts are and enjoy tracking the themes as a class.”

Copyright © 2024 All Rights Reserved Save time. Stress less.AI Tools for on-demand study help and teaching prep.

Quote explanations, with page numbers, for over 44,070 quotes.

Quote explanations, with page numbers, for over 44,070 quotes. PDF downloads of all 1,992 LitCharts guides.

PDF downloads of all 1,992 LitCharts guides. Expert analysis to take your reading to the next level.

Expert analysis to take your reading to the next level. Advanced search to help you find exactly what you're looking for.

Advanced search to help you find exactly what you're looking for.

Expert analysis to take your reading to the next level.

Expert analysis to take your reading to the next level. Advanced search to help you find exactly what you're looking for.

Advanced search to help you find exactly what you're looking for.